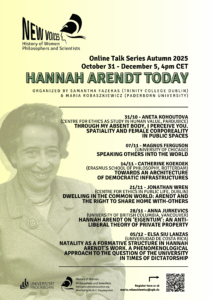

Hannah Arendt Today

The Winter Term Talk Series 2025/26, organised by Samantha Fazekas (Trinity College Dublin) and Maria Robaszkiewicz (UPB), is dedicated to Hannah Arendt.

The Winter Term Talk Series 2025/26, organised by Samantha Fazekas (Trinity College Dublin) and Maria Robaszkiewicz (UPB), is dedicated to Hannah Arendt.

Arendt could aptly be described as a thinker of the crisis, or perhaps rather of multiple crises. This motif is ever-present in her work and, indeed, it is a concept that is becoming ever-present in our own time. This is one of the reasons why academic and public interest in Arendt’s writings is currently skyrocketing. It is because so many politically acute challenges today call not for dogmatic, but for critical and practical perspectives. In her works, Arendt seems to be looking for crises: cracks in the fabric of the everyday, which offer an opening, enabling individuals to appear before each other and become political actors. It is not that action necessarily needs a crisis, but a crisis definitely needs action. Crisis, for Arendt, is always ambivalent. It presupposes a destructive moment, but also a constructive one. As she states, “The opportunity, provided by the very fact of crisis – which tears away façades and obliterates prejudices to explore and inquire into whatever has been laid bare of the essence of the matter.” A crisis only proves disastrous when the reaction to it consists of recourse to the ways of thinking prescribed by tradition, answered in conventional, schematic ways.

In line with Arendt’s critical spirit, and especially her concept of natality (every human’s capability of striking new beginnings in the world), this edition of the New Voces talk series introduces contributions of emerging Arendt scholars addressing issues of philosophic and political relevance for the world in which we live today. Topics include the female body, speech and speechlessness, dwelling and home, meanings of property, and natality in times of dictatorship. Everyone is welcome to join us in discussing Hannah Arendt’s relevance today!

Everyone is welcome to attend. You will get the Zoom-Link here or at maria.robaszkiewicz@upb.de.

The whole program:

|

Aneta Kohoutova Centre for Ethics as Study in Human Value, Pardubice |

31.10.2025, 4 pm CET |

Through my absent body, I perceive you. Spatiality and female corporeality in public spaces |

|

Magnus Ferguson University of Chicago |

07.11.2025, 4 pm CET |

Speaking others into the world |

|

Catherine Koekoek Erasmus School of Philosophy, Rotterdam |

14.11.2025, 4 pm CET |

Towards an architecture of democratic infrastructures |

|

Jonathan Wren Centre for Ethics in Public Life, Dublin |

21.11.2025, 4 pm CET |

Dwelling in the common world: Arendt and the right to share home with-others |

|

Anna Jurkevics University of British Columbia, Vancouver |

28.11.2025, 4 pm CET |

Hannah Arendt on Eigentum: an anti-liberal theory of private property |

|

Elsa Siu Lonzas Universidad de Costa Rica |

5.12.2025, 4 pm CET |

Natality as a formative structure in Hannah Arendt’s work. A phenomenological approach to the question of the university in times of dictatorship |

You cannot copy content of this page