Chapter 2 is divided into two parts: In the first part Du Châtelet presents a proof of the existence of God. The second part is about the attributes of God.

Du Châtelet’s argument for the existence of God runs as follows (InstPhy, § 19):

1. Something exists, since I exist.

2. Since something exists, something must have existed for all eternity, otherwise nothingness, which is but a negation, would have produced all that exists, which is a contradiction of sorts, as this is saying that a thing has been produced, and yet not acknowledging any cause for its existence.

3. The Being that has existed for all eternity must exist necessarily and not owe its existence to any cause. […]

4. All that is around us is born and dies successively. Nothing is in a necessary state, everything is successive, and we succeed one another. So there is only contingency in all the being that surrounds us, this is to say that the contrary is equally possible and does not imply a contradiction (for this is what distinguishes a contingent being from a necessary being).

5. All that exist has a sufficient reason for its existence. The sufficient reason for the existence of a being must be within in, or outside it. Now the reason for the existence of a contingent being cannot be within it, for if it carried the sufficient reason for its own existence, it would be impossible for it not to exist, which is contradictory to the definition of a contingent being. So the sufficient reason for the existence of a contingent being must necessarily be outside of it, since it cannot have it within itself.

6. This sufficient reason cannot be found in another contingent being, nor in a succession of such beings, since the same question will always arise at the end of this chain, however it may be extended. So it must come to a necessary Being that contains the sufficient reason for the existence of all contingent beings, and of its own. This Being is God. (Copyright © 2009 BZ)

The French original reads (InstPhy Amsterdam 1742, § 19):

1. Quelque chose éxiste, puisque j’éxiste.

5. Tout ce qui éxiste a une raison suffisante de son éxistence, ainsi il faut que la raison suffisante de l’éxistence d’un Etre soit dans lui, ou hors de lui: or la raison de l’éxistence d’un Etre contingent ne peut être dans lui, car s’il portoit la raison suffisante de son éxistence en lui, il seroit impossible qu’il n’éxistât pas, ce qui est contradictoire à la définition d’un Etre contingent; la raison suffisante de l’éxistence d’un Etre contingent doit donc nécessairement être hors de lui, puisqu’il ne sauroit l’avoir en lui-même.

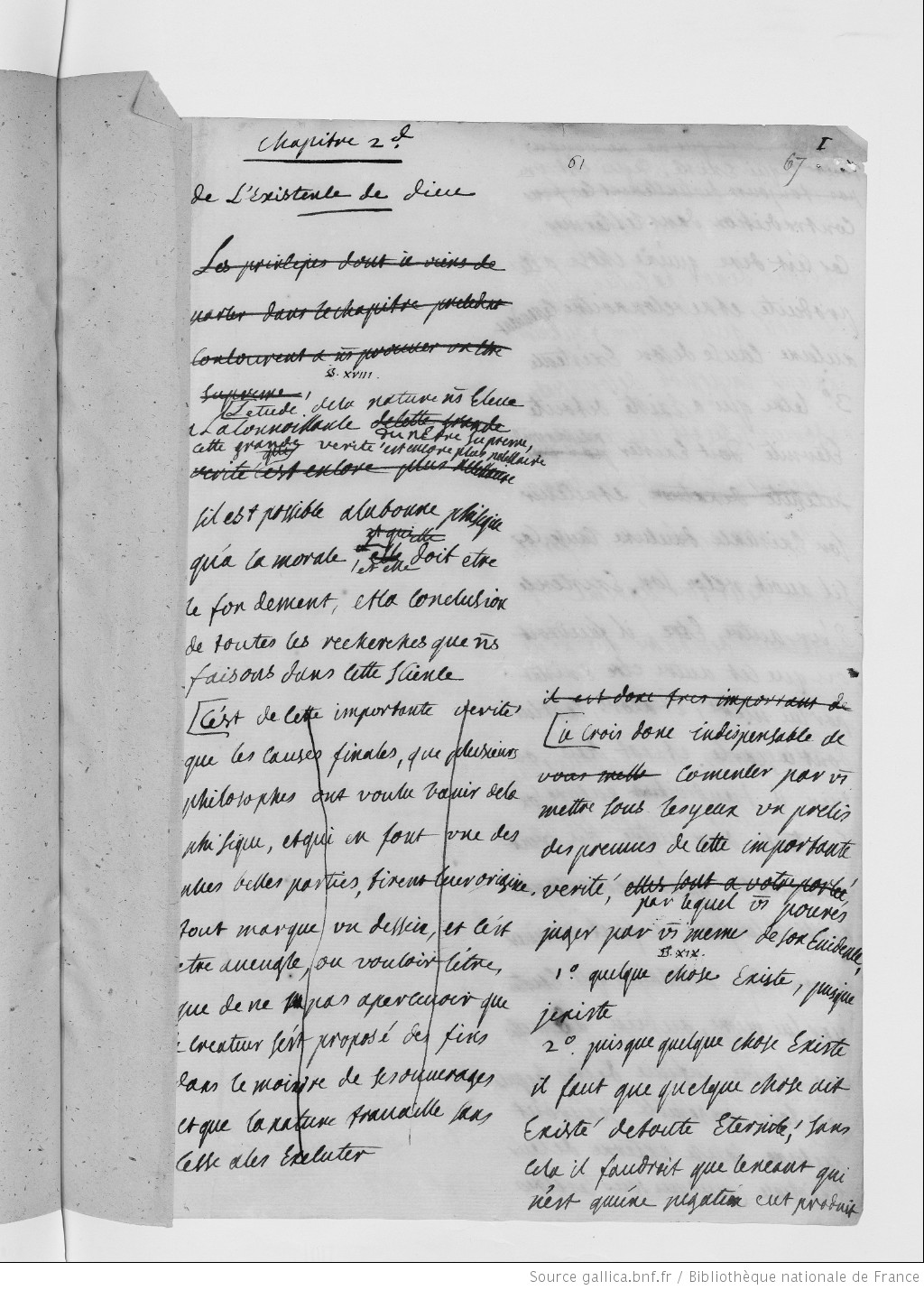

[ here is the first version, and here the second version of the Du Châtelet’s proof of the existence of God in the Manuscript Bibliotheque nationale de France (Paris), Fonds français 12265]

Du Châtelet’s proof of the existence of God was a hidden critique of Voltaire.[1] In his Traité de métaphysique, which was written about 1734-1735, but published only after the death of Voltaire, the author provides the following proof of the existence of God (chapter II):

I exist, so something exists. If something exists, then something has existed for all eternity: for what is, or is by itself, or has received its being from another. If it is by itself, it is necessary, it has always been necessary, and it is God; if he has received his being from another, and that second from a third, he who has received his being must necessarily be God. For you cannot conceive one being giving to another if he has no power to create; moreover, if you say that one thing receives, not its form, but its existence from another thing, and that from a third, this third from another still, and thus going back up to infinity, you say an absurdity, for all these beings will then have no cause for their existence. Taken together, they have no external cause for their existence; taken in particular, they have no internal; that is to say, taken together, they owe their existence to nothing; taken individually, none exists by itself; therefore none can necessarily exist. I am therefore reduced to confessing that there is a being which necessarily exists by itself for all eternity, and which is the origin of all other beings.

Initially, Du Châtelet’s proof corresponds word for word with Voltaire’s proof. Voltaire was acquainted with Samuel Clarke’s A Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God (1705) as well as with John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690/1700) and Nicholas Malebranche’s De la recherche de la vérité (1674/75). Locke had claimed that intuition gives us knowledge that we exist, demonstration gives us knowledge that God exists, and sensation gives us knowledge of the existence of other things. Although Du Châtelet might have been familiar with all these writings as well, her proof of the existence of God ends in a completely different way, by integrating elements of Christian Wolff’s proof of the existence of God, which in turn was influenced by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

Du Châtelet argues that the world is contingent, because it can be otherwise than it is. All contingent things must have the sufficient reason for their existence outside themselves. To be more precise, all that exists has a sufficient reason for its existence, so the sufficient reason for the existence of a being must be in the being itself or outside of it. The reason for the existence of a contingent being cannot be in the being itself, because if it carried within itself the sufficient reason for its existence, it would be impossible that it not exist, which is contradictory to the definition of a contingent being. The sufficient reason for the existence of a contingent being must therefore necessarily be outside of itself, since it cannot have it in itself. Du Châtelet concludes that the sufficient reason for the existence of the world must be a necessary being; who contains the sufficient reason for the existence of all contingent beings, and for its own [existence], and this being is God.

One can find the same argument in Christian Wolff’s German Metaphysics (1720, § 928): Since nothing is without a sufficient reason why it is rather than is not, a sufficient reason must be given why we exist. This reason is contained in ourselves or in some other being diverse from us. But if you maintain that we have the reason of our existence in a being which, in turn, has the reason of its existence in another, you will not arrive at the sufficient reason unless you come to a halt at some being which does have the sufficient reason of its own existence in itself. And this is God:

Du Châtelet proceeds to discuss the attributes of God. Firstly, God is eternal, i.e., having no beginning and no end. Thus, there could be no successive states in such a being. Secondly, God is immutable, i.e., without change or succession. If God were to change, then his successive states would require a reason for their existence to be found in a preceding state. But since there would be no first state, or cause for the whole, then some successive state would not have a reason for its existence, which is impossible. Thus, a necessary being cannot admit to succession. Thirdly, God is simple, i.e., not being a compound being. Fourthly, God is distinct from soul and matter. Since the existence of matter is contingent rather than necessary, there is no worry that matter might be able to provide the sufficient reason for its own existence. Nor can our soul be this necessary Being, for its perceptions, changing continually, it is in perpetual variation, but the necessary Being cannot vary. Fifthly, God must be unique. i.e., there can be only one necessary Being.

In §§ 23-31, Du Châtelet addresses the basic ideas of Leibniz’ argument for the best of all possible worlds. According to Leibniz, among the infinity of possible worlds only one actual world, i.e. our world, has come into existence. This world has been chosen by God as the best of all possible worlds. If there were no best possible world, then God would not have had a sufficient reason to create one world rather than another, and so he would not have created any world at all. But he did create a world, the existing one, which therefore must be the best possible. As Du Châtelet puts it: There must be a sufficient reason for the actuality of the world we see, since an infinity of other possible worlds were possible. God, then, is the independent sufficient reason for the world. His choice is based on his wisdom, not blind willing. Du Châtelet’s arguments concerning God’s existence and God’s attributes all rely on the principle of sufficient reason. This principle is also the proof of God’s freedom (InstPhy, § 25):

The necessary Being is thus a free Being; for to act following the choice of one’s own is to be free. (Copyright © 2009 BZ)

l’Etre nécessaire est donc un Etre libre: car agir suivant le choix de sa propre volonté, c’est être libre. (Paris 1740, § 25)

l’etre nécessaire est donc un etre libre: car agir suivant le choix de sa propre volonté, c’est être libre. (Manuscript Bibliotheque nationale de France (Paris), Fonds français 12265)

Le choix que Dieu à fait du meilleur des mondes possibles, pour lui donner l’éxistence, prouve donc fa liberté, car agir suivant le choix de fa propre volonté, c’est être libre. (Amsterdam 1742, § 28)

The fact that nothing outside of God determines him to create or act as he does clearly shows that God is an autonomous agent; he is self-determining in the sense that his actions are the result of decisions that are determined only by his own nature, which is infinitely wise, infinitely good, and infinitely powerful (InstPhy, § 28). Contrary to God, who exists necessarily, contingent beings are dependent on God’s will, which means that they can’t preserve themselves. Of course, this is reminiscent of Leibniz. However, perhaps even more than Leibniz, Du Châtelet highlights the differences between God and mankind: “man is a finite being, bounded and limited in all by its essence” (InstPhy, § 28).

************************

[1] Voltaire’s Traité de métaphysique is closely linked to his collaboration with Du Châtelet. Ira O. Wade has identified sixteen passages which Voltaire took almost verbatim from Du Châtelet’s work on Mandeville (see Wade 1947, 70-78). The Manuscript Collection of the St. Petersburg National Library has a version of Voltaire’s Traité de métaphysique with Du Châtelet’s annotations (see project). For further reading see Patterson, Temple 1938: Voltaire’s “Traité de Métaphysique.” The Modern Language Review 33/2, 261–266; Andrew Brown & Ulla Kölving 2003: Qui est l’auteur du Traité de métaphysique? Cahiers Voltaire 2, Ferney-Voltaire, Centre international d’étude du XVIIIe siècle, septembre, 85–94.

Back to main project | Next chapter

You cannot copy content of this page