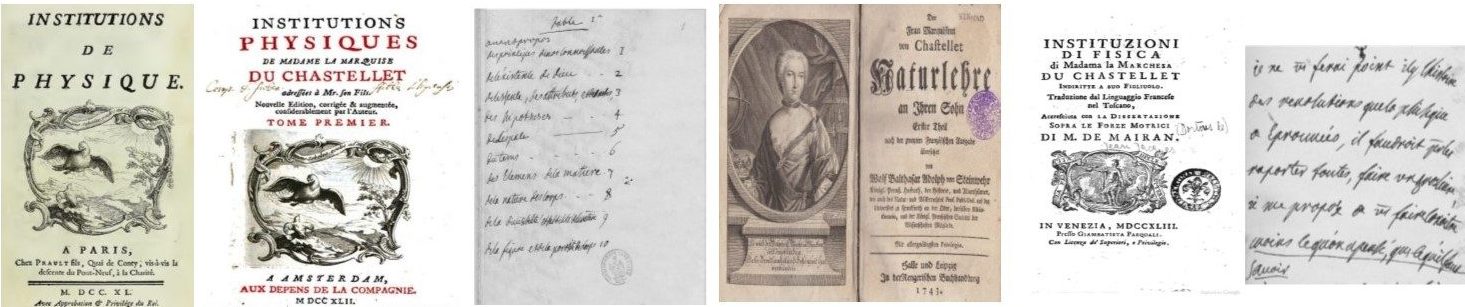

Émilie Du Châtelet is well known for her Institutions de physique, or Foundations of Physics, which were first printed anonymously in 1740. A second edition was published in 1742 under a slightly altered title, now with an explicit mention of her author’s name: Institutions physiques de Madame la marquise du Châstellet adressés à Mr. son fils. German and Italian translations appeared a year later: Der Frau Marquisinn von Chastellet Naturlehre an Ihren Sohn, respectively Instituzioni di fisica di Madama la Marchesa du Chastellet indiritte a suo figliuolo. The National Library of France has a large bound volume of related manuscript items that concern the editing Du Châtelet did on drafts of her magnum opus before it was published in 1740 (from at least 1738 through 1740).

Émilie Du Châtelet’s Institutions were marginalized and trivialized as an introduction to Isaac Newton’s physics for her young son. There is currently a movement toward correcting this historical bias. Today we know that Du Châtelet’s work was part of a critical transformation and consolidation of post-Newtonian mechanics in the early 18th century. It served as a necessary corrective to the general rejection of Leibniz by the French scientific establishment of the period.

Up untill the present day, a critical edition of Émilie Du Châtelet’s magnum opus is missing. Our aim is to present an online Reading Guide that helps students, teachers and researchers to navigate through Du Châtelet’s Institutions physiques and to make this important historical and highly original document visible to a broad audience. The project is unique in the growing research field of the History of Women Philosophers and Scientists, but it may hopefully provide a model for future projects in order to include women’s contributions into the philosopher’s teaching canon and to build bridges, by bringing texts of cultural importance to a wider audience, facilitating their translation, and allowing students to comment on their impact and significance.

Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman once remarked that their Guide to Newton’s Principia (1999) is “a kind of extended road map through the sometimes labyrinthine pathways of the Principia” (xvi, Preface). We hope that our Reading Guide will serve the same purpose: to be a road map through the sometimes labyrinthine pathways of the Institutions which critically challenges the received narrative concerning early modern philosophy.

Each chapter of the Reading Guide is structured as follows: The content of each chapter is summarised and commented. Central passages of the text are quoted literally. Each quote links to the corresponding page of the original Amsterdam edition Institutions physiques de Madame la marquise du Châstellet adressés à Mr. son fils (1742). Insofar as variances regarding the Prault edition Institutions de physique are substantively and contextually relevant, references are made to this edition. Faithfulness to the original French text is guaranteed. No silent corrections of typographical or other errors are applied, and punctuation and style are reproduced. All quotations are linked to the corresponding manuscript-page of the National Library of France. The manuscript is online accessible on gallica.

A detailed comparison of the manuscript with the two editions would go beyond the scope of the Reading Guide. Just a few remarks: The manuscript does not represent the last revision. It also does not represent the printed version of 1738, but reflects the process of revisions between the first (unpublished) print of 1738 and the printed edition of 1740. The manuscript can be roughly divided into two parts: The first part deals with foundational matters that include Leibniz’s metaphysics (and Wolff as its follower). The second part deals with Newton. It is probably that the first part was written after the second part (except the last chapter).

Comparing the manuscript with the Prault edition, Paris 1740, the following table illustrates a striking change of chapters:

| MANUSCIPT BnF | PRAULT EDITION, Paris 1740 |

| chapter X chapter VII chapter VIII chapter IX chapter X chapter VII chapter VIII chapter IX chapter X chapter XI chapter XII |

chapter VII chapter VIII chapter IX chapter X chapter VII chapter VIII chapter IX chapter X chapters VII, X, XI chapter XII chapter XX |

The chapters XIV, XV, XVI, XVIII, XIX, XXI have the same order. As Ira O. Wade in Intellectual Development of Voltaire (1969, Princeton Univ. Press) has shown, “there are in reality, three Chapter X’s in the manuscript. One is entitled ‘Des éléments de la matière’; it became Chapter VII of the printed version in 1740. Another, entitled ‘Les lois de movement en général et du mouvement simple,’ was printed and apparently corrected on the proofs. I take it that this Chapter X came from the text as it was set up for publication in 1738 and suspended. Its presence indicates that a least half of the book was set up before it was suspended. This fact, in turn, indicates that the Leibnizian half of the book and the need to revise it really did cause the suspension” (Wade 1969, p. 287). At least, four chapters of the manuscript had two versions: Avant-propos; chapter I, II, and XXI. Chapter X, XI, XII, XIII are written by the same hand, but not by Du Chatelet’s. Chapter XIV and XV are also written by the same hand, but neither by Du Chatelet’s nor by the hand of the chapters X, XI, XII, XIII. The two versions of chapter XXI correspond to two hands: Du Chatelet’s hand and the hand of the chapters X, XI, XII, XIII. The Amsterdam edition of 1742 entails one more chapter than the Prault edition, Paris 1740, i.e. chapter XIV “Suite des Phénomenes de la Pésanteur”. Further, the titles of chapter IX and X were slightly changed in he Amsterdam edition of 1742.

In 2009, Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser published a partial translation of Émilie Du Châtelet’s Foundations of Physics in Part III of Selected Philosophical and Scientific Writings by Emilie Du Châtelet, Chicago University Press (in the following abbreviated as “Copyright © 2009 BZ”). Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser’s translation includes the chapters 1, 2, 4 ,6, 7, 11, and 21 of the Institution de physique. Chapter 9 was translated by Lydia Patton; it is from her Philosophy, Science, and History: A Reader, Routledge, 2014 (in the following abbreviated as “Copyright © 2014 LP”). Since 2014, faculty and students at the University of Notre Dame have worked to complete the translation under the direction of Katherine Brading. The chapters 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 19, and 20 are now available at Katherine Brading’s side (in the following abbreviated as “Copyright © 2009 BZ”), plus Isabelle Bour and Judith Zinsser’s as well as Lydia Patton’s translations. The translations of the chapters 15 and 18 are missing. They are my own. Alternative translations are set in square brackets.

The Reading Guide has to be seen as a work in progress, which does not replace a critical edition and translation. No guarantee is given as to the accuracy, consistency, or completeness of the information.

If you would like to be kept informed on its development and on all other activities about the Center for the History of Women Philophers and Scientists, please subscribe our email list.

If you want to contribute to my Reading Guide and comment on it critically, please send an email to: andrea.reichenberger@upb.de.

For further reading:

Reichenberger, A. 2018.“How to Teach History of Philosophy and Science: A Digital Based Case Study.” In: R. Pisano, ed.: Methods and Cognitive Modelling in the History and Philosophy of Science–&–Education. Special Issue Transversal. International Journal for the Historiography of Science 5, 84–99.

Reichenberger, A. 2018. “Émilie Du Châtelet’s Interpretation of the Laws of Motion in the Light of 18th Century Mechanics.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2018.01.006

Reichenberger, A. 2016. Émilie du Châtelets „Institutions physiques“. Über die Rolle von Prinzipien und Hypothesen in der Physik. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Back to main project | Next chapter

You cannot copy content of this page