This chapter is, simple put, about the parallelogram of forces. Du Châtelet speaks of the “composition of motion” and defines this method as follows (InstPhys, § 271):

Composite motion is that in which the Body obeys several forces at once, which impress different directions on it, and which make it tend toward diverse points at the same time. (Copyright © 2018 KB)

[ Manuscript Bibliotheque nationale de France (Paris), Fonds français 12265 ]

Compare the definition of “composite motion” in the chapter before (InstPhys, § 264):

Composite motion takes place when the mobile (body) obeys several forces that make it tend toward several points at the same time. (Copyright © 2009 BZ)

[ Version I: Manuscript Bibliotheque nationale de France (Paris), Fonds français 12265 ]

[ Version II: Manuscript Bibliotheque nationale de France (Paris), Fonds français 12265 ]

Following cases are distinguished (InstPhy, § 272):

- Two forces act in the same direction: The resultant force is in the same direction as the two forces, and has the magnitude equal to the sum of the two magnitudes. Consequently, the direction of its movement not being changed.

- Two forces are equal and opposed to one another: The resultant force will be zero because two opposite forces cancel each other out.

- Two opposing forces are unequal, i.e., they cancel each other out only in part, and the resulting motion is equal to the difference between the magnitudes of the two forces.

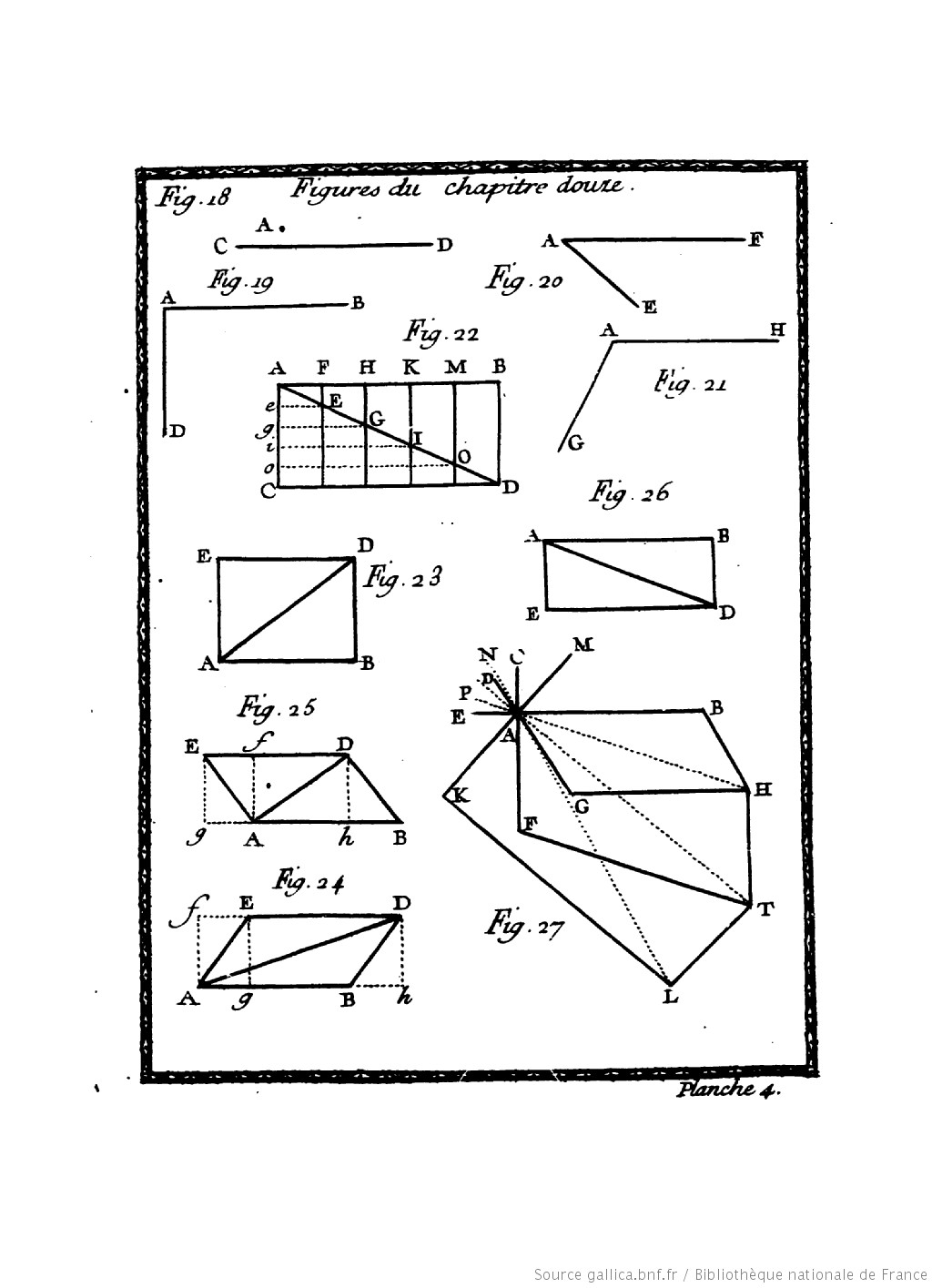

- Two forces that are not parallel, but perpendicular to one another other: they will neither cancel each other out nor accelerate. {Fig. 19, Plate 4}

- Two forces are oblique to one another: they will retard or accelerate the motion of one another, according to how the obliquity of the Lines that represent them will be directed, and they will have moreover an action that is perpendicular to one another, that will neither accelerate nor retard the motion of one another. {Fig. 20, 21, Plate 4}

[A number of further cases are discussed in §§ 273-282 {Fig. 22-26, Plate 4}]

When more than two forces are involved, the geometry is no longer parallelogrammatic, but the same rules apply. In today’s teaching practice it is taught that forces, being vectors are observed to obey the laws of vector addition, and so the overall (resultant) force due to the application of a number of forces can be found geometrically by drawing vector arrows for each force. However, one should not forget how novel this method was with Newtonian physics as a backdrop.

In Newton’s Principia, the first corollary (Corollary I to the Second Axiom) that appears after the three laws shows how forces are to be composed:

Corpus viribus conjunctis diagonalem parallelogrammi eodem tempore describere, quo latera separatis.

A body acted on by [two] forces acting jointly describes the diagonal of a parallelogram in the same time in which it would describe the sides if the forces were acting separately (transl. by Cohen/Whitman 1999, p. 417). Some pages later Newton applied the parallelogram composition of an inertial motion and a centripetal attraction for the problem of circular motion and centripetal acceleration.

The importance of Newton’s parallelogram composition of an inertial motion and a centripetal attraction becomes obvious regarding circular motion and centripetal acceleration. When an object moves in a circle at a constant speed its velocity (which is a vector) is constantly changing as viewed by an observer in an “inertial frame” (the frame in which the circular motion is taking place). Its velocity is changing not because the magnitude of the velocity is changing but because its direction is. This constantly changing velocity means that the object is accelerating (centripetal acceleration). For this acceleration to happen there must be a resultant force, this force is called the centripetal force.

After describing a curved line as the change of the direction at every moment (infinitely small instant), Du Châtelet defines the centrifugal force as follows (InstPhy, § 291):

If the accelerative force suddenly ceased to act, the Body would continue to move in the right line along which it would find itself directed at that instant; for every Body moves continues to move in a right line and with equal speeds as long as nothing hinders it according to the first Law of motion (§ 229). It is in following this law that every Body that moves in a circle tends to escape along its tangent; and this is what we call centrifugal force. (Copyright © 2018 KB)

[ Manuscript Bibliotheque nationale de France (Paris), Fonds français 12265 ]

The chapter ends with an example for circular motion, namely Earth’s Rotation (InstPhy, § 292):

There is yet another type of circular motion. This is the relative motion of a Body that rotates on itself, as the Earth, for example, in its diurnal motion: this is made, then, by the parts of this Body that tend to describe the infinitely small straight lines of which I have just spoken (§ 290). One can define this type of circular motion: a motion in which the parts change place, although the whole does not. (Copyright © 2018 KB)

[ Manuscript Bibliotheque nationale de France (Paris), Fonds français 12265 ]

******************

Compare the ENTRY “Mouvement” in the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences (1751 , Tome 10, pp. 830-842): “There are still many comments to be made on this vast subject, but this book is not susceptible to further details. We can read chapters XI. & XII. of the Institutions physiques de Madame du Châtelet, from which we have extracted part of this article; M. Muschenbrock’s Essai de Physique, and M. de Crousaz’s Essay sur le Mouvement, which was crowned by the Académie des Sciences, & several other works.”

Back to main project | Next chapter

You cannot copy content of this page